Towards Citizens Enablement (Draft GF)

After Covid-19, Academics should Enable/Empower

Citizens to achieve their aspirations

The Essence of

our Proposal

Academics have the capabilities to enable citizens’ self-learning in order to empower them to achieve more for themselves. Those in current need must own their problems and issues, and by practical means, learn to embrace them & enact solutions. The innovative capabilities of both academics and citizens can be combined to solve almost any issue facing a community. Our studies of best practice show what can be achieved across a broad range of problems. For significant changes to occur, the values and behaviour of all collaborative partners – who have often in the past come from competing sub-cultures – must be combined, using a questioning framework, so they share ideas that lead to sensible working practices, and then enact feasible outcomes.

Traditional Interactive

Paper Digital

Form Form

The Enablement of Citizen Playbook

A developing conversation between James Powell and Peter Palme –

a step by step-by-step & non-threatening magical path to the better world of Citizen Enablement.

or how to create a deep, meaningful and lasting empowerment in citizens and communities, to enable their own self-development in order that they might achieve their desired ends

0.Introduction

This paper has come out of a deep and meaningful discussion between the two present authors, both Leonardo Ambassadors, where Peter Palme indicated his wish for James Powell to create a blog, showing what Peter called the magic points for Citizen Enablement. For many years, James had been attempting to develop an approach which truly enables University Academics, with the right interest, to develop a better way of empowering disenfranchised and often poor citizens, so they could control their lives in a more fulfilling way, for their benefit and those of others in their communities. This paper developed as a result and tries, what both began to call, the development of a magic playbook for Citizens Enablement. While far from being magical, the approach in the paper does try to lay down a few ‘home truths’, to those who wish to develop a more appropriate way of supporting citizens in an important new journey which should also enable their own personal wealth to increase as well as their well-being and contentment.

1.Executive Summary and the Logistic of the Paper

Hopefully, to ease understanding by the reader, we quickly, but briefly, summarise and reveal the structure of the paper now.

- Firstly, the aspirations for the approach being used is clarified to let the reader understand ‘why’ the work is the way it is and it’s particular intentions. In short we are inviting readers to participate in a big “paradigm-shift” away from the current ways of thinking, being and working, particularly in universities by supporting academics involve citizens in their learning of how to become masters of their own destinies.

- The sociological perspective, ‘the cultural why’, upon which the authors base their arguments are spelled out which leads onto the drive for Citizen Enablement by listening Academics; and we clearly include in the word citizens, all presently the disenfranchised, including Black, Asian, Minority and Ethnic groups, women and the young, but for simplicity of presentation we will only use the term citizen for all such communities in the remainder of the paper. However, it goes without saying, the paper recognises that not only do Black Lives Matter, but also Women’s Lives Matter, or All Lives Matter or even “ALL LIFE MATTERS.”

- James is more than aware that we have built our educational and economic system on the basis of “competitive individuals.” But the paper wishes to “enable” and support all of us in “meaningful”, and perhaps “meaning rich ways.” We both also believe that in our proposed developments we will have to move from money to meaning, and from profit to purpose, in this new era, although wealth will still be necessary to make any developments work in the real world. It is also clear from the successful cases shown in Part II that the most effective progress is to tackle small and handleable projects within the grasp of all collaborators, while being aware of global consequences.

- Even tackling small issues, no one should underestimate the cultural change that must take place to ensure successful collaborative working between all these citizens and academics, so in the next section of the paper much consideration is given to this difficult process engendered by our suggested approach; hence the papers reflection on the word destiny which James uses in a forward looking sense to define the passionate way he believes is necessary for all of us if we are to ensure success in complex and difficult ventures.

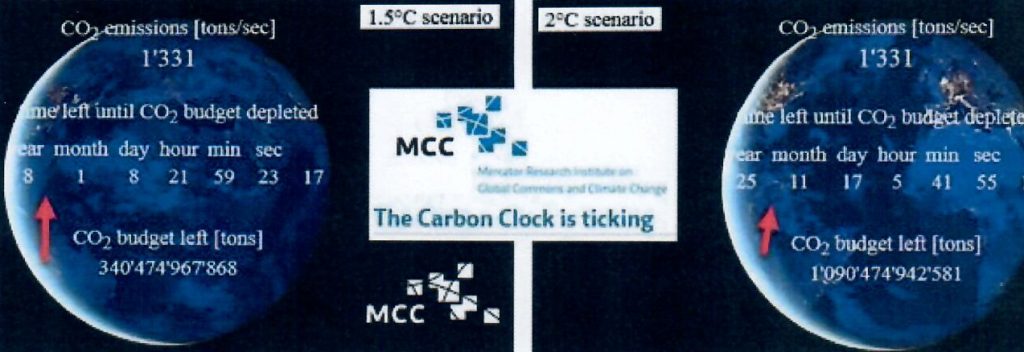

- Implicit in the paper is another recognition – a deeper ‘why’ for all now in society – the need for developments which are truly sustainable, because it is clear to us that there is only a TEN YEAR Window of profound rethinking, exploring the very foundation of our human civilization, otherwise we will be drowned in our irresponsibly created CO2. As we all already know, according to the MCC Carbon Clock (see below), we have only eight years to make a major change in direction for human history if we want to stay at 1.5° C or less, and about twenty-six years to stay within 2.0° C. In all our cases reported it was clear that the citizens being empowered were well aware of this and wanted their developments to show the necessary sustainability as well as satisfying their other needs and wants. Our challenge, and that of the citizens we are trying is to help is HUGE, because the momentum, especially of the last seventy years, is so intense.

These are large issues that Academics are often fond of, and good at, considering, but they will normally be beyond the scope of a Citizen Enabling project. They are important to bear in mind, because they will set some underlying parameters of what should, and will work, on any project for both the citizens themselves and the planet as a whole.

- A step-by-step approach, which the authors propose, showing ‘what’ and ‘how’ to achieve necessary change, is now laid down in a straight-forward way, for Enablers and Citizens to plan the way forward with concrete actions; in short it shows how you too can become an Enabler of Citizens, and hopefully Empower them also.

- Collaborative working starts with a reflective period where the relevant citizens are invited to join, with others of like-mind, and their (academic) enablers – who themselves must identify citizens needs and wants, their capabilities and the change development teams require; such teams are not the competitive ones of sport, but more ‘reflective communities’ [or RefComs as Charles Savage (2020) would call them]. The passions and visions of each team member, in such a joint enterprise is a vital first step, as it sets the scope and boundaries of any potential venture;

- Members of such a joint venture have to understand their aspirations first, then those of their colleagues and finally how to get the best from team working. They have to learn ‘how to learn’ to undertake the skills missing from their team or find someone who can complete their change needs, and also recognise they may well have to be politically and socially astute if they are to enable change to be possible at all and then become empowered to fully enact it;

- Evaluating a development teams own situation regularly is necessary and can be achieved, using easily available and cost effective tools, to understand a developing processes, first hand; academic and citizens might well need such evaluations, related analyses and any other feedback to be in their own readily accessible language;

- Active listening and understanding is vital and the key to successful Citizen Enablement. Deep and maturing conversation between all members of any collaborative development will ensure overall understandings are shared. It is also important that such developments are undertaken by the whole team, so that all understand precisely what has been achieved and what needs to be done to satisfy citizens needs and wants. Also, any collaboration should try to find whether the present solution sought has been achieved before, so all can learn from those who have done it already, in a constructive way, and to repeat best practices, learning from similar successes elsewhere; this is known by others as ‘positive deviance’.

- Success must be for the citizens themselves to decide, and in their own terms, however such citizens should never cease to strive for continuous improvement. However, successful projects normally start small and build over time – taking on too much may doom a project to failure,

- Sensitive and citizen focused leadership is key to creating a new enterprise culture that works effectively by satisfying everyone’s needs and wants. For three major reasons:

- enterprise change collaboration requires the bringing together of more than one differing cultural aspiration; balancing those cultures is a key element for a leader to cope with – leadership for cultural change;

- the focusing of sometimes competing team members values and behaviours, so they become reflective communities, on complex projects or programmes often feels impossible to understand to begin with, let alone deliver, but it must be done.

- Academic Enablers must show leadership that focuses on some key processes in order to drive Citizens to: firstly to become Enabled for themselves to work out a solution to their problem or issue, and then become Empowered to ensure their development is enacted in the real world.

- Sensitive and citizen focused leadership is key to creating a new enterprise culture that works effectively by satisfying everyone’s needs and wants. For three major reasons:

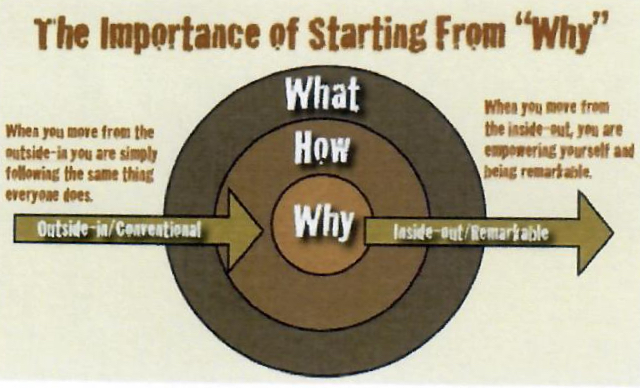

- Before they embark on their collaborative venture academics and citizens firstly need to understand the ‘why’ of what they want to do, and then agree the how discussed above.

- The Human futures after Covid-19 will be very different, and universities, for instance, will need to become a “reflective centres” for all ages (not just “Executive Education), so we can tap the wisdom of the past and envision a wiser future. So the paper suggests a shift from SMART to WISE.

- Perhaps, and even more severe than the corona pandemic itself (demeaning prejudices, discrimination, petty nationalism, plus locust, inequality, displacement, recessions and so much more) is our present ignorance pandemic (the propensity for hindsight). Are we not failing to see, sense and understand what we must all have been aware of for years?

At the end of the paper, in Part II, are presented 17 cases of best practice, with evidence to show what can be achieved by those willing to take part in Citizens Enablement. While not a trivial task we have shown it is entirely possible for us to adopt a different an d highly successful approach at living after Covid-19

Let us deal with each of those overall characteristics of a successful project development in a little more depth relating key elements to the highest values revealed by the different case studies.

2.Central Aspiration of the Authors or ‘Why’ we are doing this.

After Covid 19, many Citizens may feel it is worth trying to develop a recipe for a ‘new normal way of working’, where one size does not fit all, but they become Enabled to change their local world, for personal benefit and that of their fellow citizens. The present authors believe we are at a time and stage where to try new ways of working are entirely now possible and by way of example look at the current take up of video conferencing/zoom during Covid 19, when the technology has been available for over 25 years. The journey of self-development and enablement, as with anyone, starts with oneself and locally, at any time you are ready. There is no need to wait for the fairy tale, good fairy, to come to the rescue. Ideally it will also lead citizen to become empowered to enact desired change.

In terms of a participation in decision making, we believe that the better educated, representing about 35% in a country like Germany, are more likely to participate in local constituency democratic decision making processes; this is according to an article on social practice in “Der Spiegel” (2016); whereas the research on participatory democracy by Parry (1972) suggests that the uneducated seem to depend more on stealth and direct democracy, rather than democracy through active participation. However, we need to improve such a situation for the disenfranchised.

Citizens Enablement might well be a Utopian dream, but now might be a good time to help create a different future for citizens and communities and accept the recent studies undertaken by the Royal Society Arts which begin to show how this could be achieved. This is no matter how difficult such a cultural change might be, as it will involve social, as well as personal, interactions and therefore changes in social relationships. It is clear that different cultures will require a different type of societal contract, for the world does not any more create a linear perspective for the development of anyone. But now is at least the time to try to enrol and engage citizens in a better way.

The PUMR approach on which this paper is based was honed into good working practice by the PASCAL International Observatory (Generic Process B, page 31). It was designed, bearing in mind normal cultural biases, and has been shown to create Citizen Enablement of the highest order. So, for instance, both Peoples Voice Media and Community Reporters projects (Case Studies 4 and 8, pages 50 & 59) show how citizens can, and do, give full voice to their own needs and wants.

3.The Sociological Perspective that drive James’s desire for important cultural change for the ‘Good’ of all Citizens – their ‘Whys’

From James’ perspective, early in his career he became aware of the work of social anthropologist, Mary Douglas (1966), and one of her disciples, Michael Thompson. Their work indicated that different cultures have different ways of seeing the world, and thus acting in it. Their research comprehensively showed that there were four constructive alternative ways of doing this. So, when others didn’t believe in the way James saw the world, he could begin to understand why. Such cultural constructed world views explains, at least to us, that whatever skills we possess in developing human futures, we should try to truly reflect what others want for themselves, and not just what we want for ourselves alone. It is because of this that James continues to be concerned with, and passionate about, enabling others achieve that which is meaningful to them and the empowering to enact it, while ensuring this allows harmony with the rest of us. Let’s not control, destroy others or harm them.

As an important aside, reflecting this in a different way, Sir Antony Gormley, the creative British sculptor, said recently on Grayson Perry’s TV lock-down Art Club, ‘we are all makers of art! There is no pinnacle to our creativity, for me, or for anyone. Everyone can reveal their creativity in their own way’. This, to James, is the same for all Citizens, in whatever they strive to achieve, or want to strive to achieve. So those who can and want to help Citizens Enablement, particularly those from higher or further education, should, in our view, try to do just that, so we need to understand if anything constrains this. We also need to recognise that higher education empowers some – by creating an elite – so simultaneously disadvantaging others. And this is what Michael Young meant when he criticised ‘The rise of the meritocracy’ (1958).

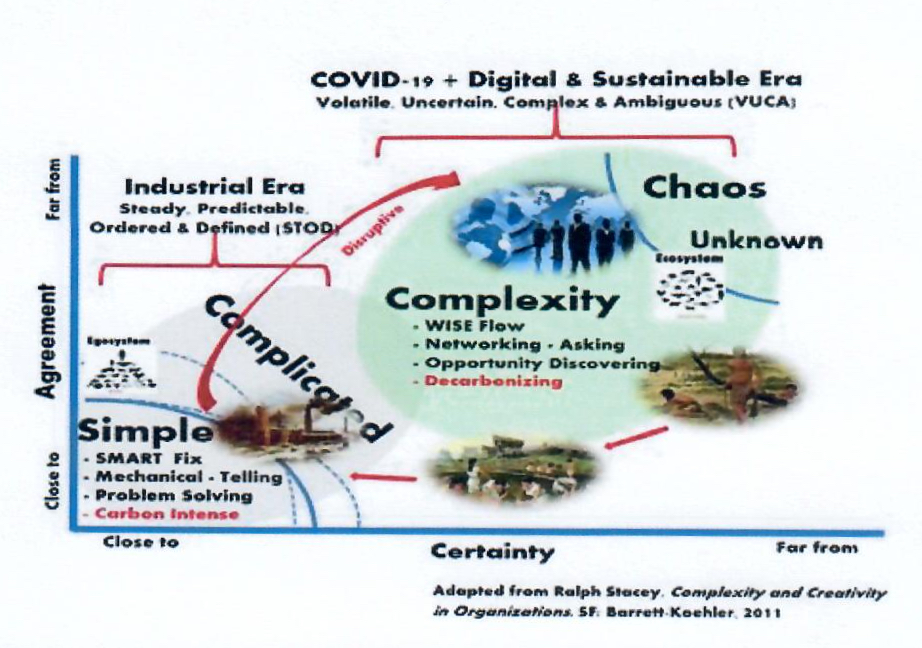

However, and to put this in perspective, the problem of developing change is not simple, rather the future is complex and requires those of us, who want to help, to think more systemically, about how we drive a change where the enablement needs to be personally contextualised. This is at a time when education often seems increasingly about the narrowing of what is on offer, to the lowest common denominator, for reasons of economy. In particular, we have to use our improving teaching and learning skills, resulting from meaningful research, to lead citizens to learn to learn for themselves. This has never been more possible, and perhaps even necessary, at a time when our societal context is so open, and where the future situation is almost experimental and where everything can be at stake, it is now just worth a try at the new. But, we all need to keep optimistic and keep trying in the face of adversity. What we also need is ‘excellence in diversity’ for all our educational and learning support. And, we repeat, it won’t be easy, especially as we watch social and political life crashing about us, now. This is where facilities like the Salford Innovation Forum (Case Study 9, page 62) come into play, as they provide a context, people and facility which enables innovation to start, grow and flourish for local citizens.

James has particularly found it possible to use whatever skills he has simply to help other citizens and communities learn to do better for themselves; at least the ones he works with seem to think that to be the case. He sincerely hopes others in Leonardo will do like-wise, as he sees them beginning to think this way in all their recent Leonardo discussions. Both the present authors would welcome the opportunity of developing a maturing conversation with like-minded people, who are well grounded in what Gramsci (Forgacs,1999) would call ‘good sense’ or the quality someone has when they are able to make sensible decisions about what to do . While it is important that we should all be richly engaged in discussions reflecting powerful world-wide views, if we cannot also be well anchored locally, as if we were stable in one place, we believe all our efforts will be in vain. The Action Learning which is used in Case Study 6 (page 54), in a project known a ‘Bouncing Higher’, shows how citizens can truly be supported in their cross fertilisation of best practice working to enable small business to develop better innovation and wealth creation.

4.First Steps towards Citizen Enablement: from ‘Why’ to ‘How”

The most important first step in any project seeking to engender Citizen Enablement, for both academics and citizens alike, is the need to understand the ‘why’ of what they want to do, before they agree the ‘what’ or the ‘how’. Increasingly, for many academics their ‘why’ question may well start from wanting to help disenfranchised citizens take control of their lives, enabling them to develop a more contented existence. For Citizens it may be their only chance of ensuring they can develop a future relevant to themselves, or people like themselves. Marcus Rashford, the number 10 for Manchester United recognised this when, with a passion yet humility, took on the British Government to convince them to provide free meal vouchers for the poor people of the UK; before he was rich and famous he had been from a poor single parent family suffering the same plight of many today. So he took on their cause, as originally a citizen like them with the knowledge of their situations, and convinced those in power to change their rules to ‘what everyone else knew to be right’. So he knew his ‘why’ of what nobody else had picked up on.

So, as Socrates so rightly said, for citizens and their Enablers, the key is always to be clear about their purpose; this lies at the heart what they might do together and the kind of leadership needed to make it happen. You first must know ‘Why’ – why you are doing what you do, how it fits with your values and enables you to create a deeper and more enduring sense of purpose. And for the leaders of collaborations for change they have to do things ‘on purpose’. It requires a sheer force of will, and a determination & persistence without which visions are mere dreams. So develop better ‘Whys’ for yourself, and the new Citizen Enablement challenges; see below for a diagrammatic presentation of the importance of ‘Why’.

Knowing ‘why’ will define your own goal and give you the motivation to create the best life can offer you. Without having confidence in your ‘why’ behind you, your chance of realising your goals and dreams will be minimised and will leave you in a position where it will be easy to quit. So Citizens need to know their ‘Whys’ as do their academic supporters. Once everyone is clear of ‘why’ they are undertaking a collaboration they can begin the process of any development. Why future problems and issues have to be undertaken by collaborations is that today’s and tomorrow’s solution will require an understanding of complexity and perhaps even chaos.

So lets now begin to consider the ‘how’ and ‘what’ we might do to begin any successful Citizens Enablement.

- Reflection:

Peter’s first question to James when they started their discussion on what he called a ‘magic question’, because it opened up something unexpected to him, was ‘Are you in control of your own destiny with respect to Citizen Enablement? Rate it from 1 to 10. 10 means you are in total control and 1 of course you have no control. Peter’s remark to James was: he had searched the internet for a survey – the only found one so far: Locus of Control Example https://www.surveyshare.com/template/352/Locus-of-Control

James hopes he can rate the control of his own life, and his future, at around 9 on Peter’s scale. But he further believes it should be important for most of us, including himself, not only to be in control of their our own destinies, but, more importantly that others should not control us. And as Der Speigel said, the 35% who are well educated, are in a position of easier personal control because of their skills and capabilities; they may not need our support, but they might also be in a position to help others. James feels he is one of the lucky ones in this respect. However, it may be that everyone may not have the ability/skills to be able to be in control or to communicate this to others. But many more citizens James works with seem able to be in greater control of their own destiny after initial support; for instance he worked with young persons’ with disability issues so they could develop their own social networking system for themselves that was truly mind blowing (Powell, 1997). Furthermore, Contraception: the Board Game (Case Study 3, page 46) shows how, even the young can take control of their own, sexual lives, and learn to share best practices from fellow young people using the best principles of ‘positive deviance’; positive deviance (PD) is an approach to behavioural and social change based on the observation that in any community there are people whose uncommon but successful behaviours or strategies enable them to find better solutions to a problem than their peers, despite facing similar challenges and having no extra resources. Barbara Hastings-Asatorian used UPBEAT evaluations and observations from the young learning about contraception to continuously improve the effectiveness and marketability of her developments until she became an acknowledged world leader in her chosen development area; this is a good example of positive deviance in operation of this case study.

However, many poor citizens are in communities that feel they may well be disenfranchised from controlling their lives, almost like those in concentration camps where their guards control their every action. Rather, these people stand back from any decision making which might enable real change for themselves – as Mary Douglas in Purity and Danger (1966) would say ‘to them life is like a lottery’ – only a lucky chance could ever make any real difference to their lives. When we start with such citizens, at the early stage of any project, few of them actually feel they have any real control, but by hard work of an Enabler – a person who makes things possible – this changes positively, for nearly all citizens (see Victor Frankl’s “man’s search for meaning?”, (1999). So unaligned citizens may well become true stakeholders in their own futures sharing a real vision with fellow citizens and knowing precisely what’s at ‘stake’. So, for instance, the Community Banking and Community Land Trusts projects (Case Studies 1 and 7, pages 34 & 66) show, with a little initial external support, citizens can truly develop professionally managed facilities, normally only open to those from a very different culture.

Peter then further asked James:

- What does it feel like to be above 6, related to the question of controlling your own destiny?

- And when you feel in control of your own destiny, how can you start to help others be in control of theirs?

According to James, life is about a continuous process of striving to be in control. So for him, he is continuously trying to become a person who endeavours to help others and use whatever skills he has, at the local level, to help other citizens achieve their own enablement, then becoming empowered to enact change and thus enhance their personal desires.

So then Peter asked further: How would you define destiny? To Peter, who is passionate about continuous learning & development, that is his main driver and enabler for wellbeing, sustainability and peace. And, since his university studies, his research and participation in European Projects, he has been involved in continuous learning & development. Peter supports this by technology, so the learning provisions he offers can be easily scaled and accessed globally. Now he works as internal development consultant in the Migros IT department, with the focus on enabling HR Transformation supported by SAP Success Factors Cloud Technology in the core administration processes of HR (see Peter Palme’s CV in Part III). Like Peter, James, has a love of adult learning, as a life-long Academic with a real interest in adult and continuous education. His early years were stymied by academic failure, but he was lucky enough to change all that and to go to university in Harold Wilson’s ‘White Hot Technology’ of the sixties, when anything seemed possible. He studied at UMIST (University of Manchester Institute of Science and Technology), which it’s Principal Lord Bowden considered to be Britain’s MIT, he found the joy of higher learning for himself and was guided by academics who helped him pass that love onto others. So, to him, destiny is not what’s life meant to be initially, or what’s written in the stars or an inescapable fate. Perhaps a better way of looking at the destiny issues is to ask the questions “who are you trying to please in what you do or what do I really want to do for me?” Peter says some ‘people might believe they have as set destinies at birth, more like a fate, or for others, who are diagnosed with a fatal disease that will likely will cause their death in a certain time frame’, and may believe that is destiny for them. Yet Peter goes onto say divine fate may well exist but, even in this situation, ‘they still have control over the journey towards it and in some instances might even prolong or possibly change the outcome circumventing their projected death.

This is not the destiny James believes in, as he doesn’t feel it is something that happens to you by divine decree, or fortune, but rather because of your living conditions and personal situation. For him, his newly found destiny started when he considered a new direction to live his life. The ICCARUS project (Case Study 13, page 71) shows how normal citizens, including normal but bright fire officers often with poor academic learning, can become the managers of major fire incidents; and the leaders, and developers, of suitable educational aids can learn to use advanced IT systems to make this occur cost-effectively.

The two different views of Peter and James reflect a humanitarian/religious split but there are similarities in both in relation to the ‘control’ one can exert in either journey. So, what are the choices we all make and how are they derived? James is clearly aware of the awkwardness of using the word destiny in his context, but to be able to fulfil the difficult tasks of changing a culture when driving for Citizens Enablement and then Empowerment, changing living conditions, requires vision, persistence and passion which become a sort of forward looking destiny; necessary if such a leadership is to work. Such characteristics are required as the catalyst needed to tackle and solve the undoubted obstacles to change whether that be luck, political power or, indeed the support of a social enabler/mentor. For James however, once you have found your own values in life, maybe even through serendipity in his case, destiny, in this forward looking sense, starts to be your confirmed way of being and doing, no matter in what circumstances you find yourself. It requires you taking speedy action and responding quickly to the result and then repeating success regularly. This sort of destiny may not begin as the pre-ordained path of your life. However, if you are to survive in a world that may wish you not to change it must become your destiny. Then, with patience, persistence, effort and vision, you will find a way to suit you; it can become your way. As Gormley says, which was reported earlier, you too can become a maker – a creative in your own right or someone who can learn to make the future they desire in any sense of that word. It could be as simple as giving and sharing your love with everyone you meet. Or when you are living out your purpose in life, you start living your personal meaning of destiny. When you are aligned with your destiny, your life is joyful, delightful, exciting, and fulfilling. So, this is what James means by his destiny and he sincerely believes everyone should try to find theirs and a way of life that is right for them. Only fear and negative imagination may stop us, but we have to work around that. His way, because of his interest in life-long learning, is to help others find theirs, or at least show them how to begin to realise there is a destiny of this kind for them. With hindsight he may have chosen a better word to describe this underlying characteristic he believes is so essential. So for instance he might have chosen the word ‘calling’ which the renowned British individualistic photographer, Michael Parr, used about his acquired drive to achieve. Or he could have used the notion of (self) efficacy – how well one can execute a course of action to deal with prospective situations Albert Bandura(1982). Taken together these views mean much the same to James, who sees them as relevant antonyms, alongside will, volition, choice, deliberation and the like, to describes the power of how he now feels. The Smart City Futures project (Case Study 11, page 68) showed how local citizens could similarly gained control over their own destinies through a conferring process that enable them to share ideas with each other in their own terms.

4.2 Understand or define your position first, listen closely to those citizens you wish to enable and CHANGE your own position first, to meet their needs

Typically, little normally changes to the environment you perceive, or in your own behaviour – anyway that which gives you a real sense of progress. However, you must strive to take control of what you can control and drive to improve your lot. But James believes you should, avoid changing others first, until you’ve first changed yourself.

Peter then asked James:

- “How does it feel right to you when you sense an increase in self-development and control over your destiny or the journey to your destiny?

- ‘How does it feel wrong: If you feel blocked, upset, or frustrated because you are waiting for others to act. Especially if is a larger issue that first seems too big for you to feel any control or influence over – e.g. global warming, etc?

James believes you begin to feel different, by starting to work out your own position and values and then find like-minded people to work with, who feel as you do. This is exemplified Steven Covey, who revealed the important characteristic of the 7 habits of highly effective people (1989). There might even be Citizens who already have the skills to help achieve their own ends, and then you need to work out a way of helping them. But, even when citizens don’t already have the confidence to try the new, again listen to their needs and work with them and you will find a way. This requires a great deal of listening to their needs, desires and wants and working with them to develop a way to enable them to achieve their desires, eventually by themselves. It may take time, but it’s worth the effort; this is supported by the work of John Forester in the planning arena on what he termed as the ‘deliberative practitioner (1999). Along similar lines the SEEE Oxford paper Wim Veen recently introduced to the Leonardo team, and an except shown in Annex1, gives some clues of how this might work after Covid 19 for the area sustainability. And nearly all the cases studies in Part II show how citizens can be empowered and then enabled to develop changes for themselves of value to their communities putting personal ideas into ventures that work in practice.

4.3 Analysis

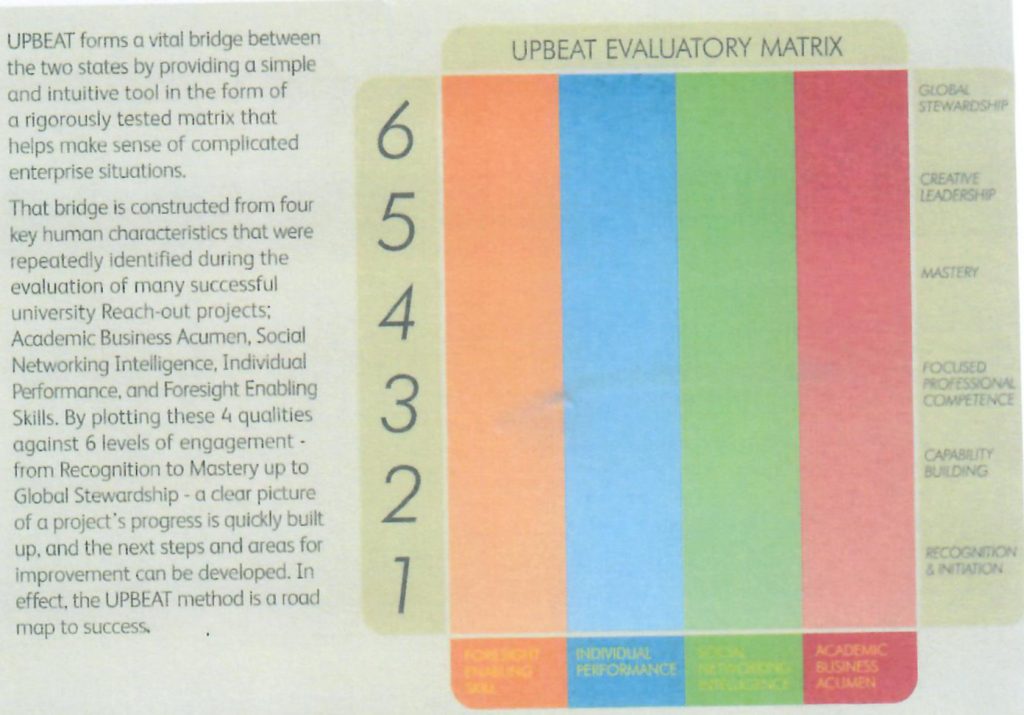

It is important for those wishing to help others, firstly collect as many facts as you can about those you want to work with – including understanding what it is in their circumstances that prevents them from achieving their aspirations and the social, economic and political constraints on their actions and skills that can be used to help them; whether they be citizens, small businesses and communities; you really need to get to know their needs desires and wants. You have to see what each citizen in any community is already, or could be, capable of achieving by themselves, what they never will be able to do and how your skills can be used to help them learn how to do things for themselves. It is particularly important to ask open questions of understanding to guide your ways of helping their SELF-ENABLEMENT. This is far from being a trivial task as the skills, capabilities and authority of those professionals presently in control provides them with a structural power that is difficult to overcome or rebalance, particularly in the UK. Whatever the problem, in order to understand the progress you are making in any development, as citizens try to rebalance things in their favour, it is necessary to evaluate what has been achieved, give feedback to the developers of change and what needs to be done to ensure proper Citizens Enablement. In this context, all the cases presented later all do this using the same general principles that were developed in the UPBEAT project (Generic Process A, page 26); in particular, this is normally undertaken using its matrix to visualise team and project development in a fairly gentle, but clear way; this uses and evaluator process with a linked questioning framework to guide Enablers and Citizens with a sensible way of approaching any problem or issue. The value of this evaluation and it’s associated analyses were validated on over 250 successful projects undertaken across Europe and built into the generic approach adopted by the PASCAL International Observatory known as PUMR, and seen in more detail in Generic Process B (page 31) and on web-site http://pumr.pascalobservatory.org.

4.4 The Key to Enabling Others – an important reprise

We repeat, the most important way to help Citizens Enablement is by listening closely to those Citizens and adapting your own ways of interacting with them so you can help them deliver what they want, rather than what they can realistically obtain. This clearly raises an important issue of how to raise both Enablers and Citizens aspirations to want the desired changes, and to enact them, without extending their expectations of what is a critically achievable in practice. There are certain Sustainable Development Goals we might all strive to achieve, such as Guenter Koch’s ‘Economies for a Common Good’, but we all must make sure what we strive to do to help Citizens achieve is what they actually want, and not what you might think they might want. This is not a trivial task to cope with but it is a critical issue bearing in mind while working with those you are seeking to empower; failure to match aspirations with realisable expectations easily leads to disillusion and this is where the capable Enabler/facilitator has a real role to play.

The base line for the sort of Citizens Empowerment, that James eventually strives for, must begin with Enablement, since he has a selfless desire to help others, to truly help them define what they want for themselves and then achieve it. He realises it will be difficult to achieve the full, more radical and politically questioning form of Citizen Empowerment, since it will require a redistribution of power from those who have it already. Enablement, on the other hand, can at least can mainly be achieved without radically upsetting the status quo, although any change impacts the status quo to a greater or lesser extent; . However, you only need to listen to the needs and wants of citizens to realise those in power rarely ceed their authority, to others, including citizens and communities, however, as we show in Case Study it may need the Enablers to become politically aware to deliver some change, some of the time. Enablers having professional, or other skills of those in power, need to use their understanding of those in power to enable them to help citizens achieve their own ends. Such active listening avoids the desire for those professionals, who know what should be done, to ‘fix’ things the way we would normally do. The HART project (Case Study 11, page 66) shows how a fun game could empower, lay volunteer controllers of Housing Associations, to properly ensure their duty of care was honoured in the control of a third of Britain’s housing is well managed and Unlimited Potential (Case Study 5, page 52) shows how normal citizens and even those with disabilities can take control of their own destinies.

- When is it successful?

The recognition of success is when the citizens show they have actually achieved their own ends and, ideally, start passing this enablement process to others – themselves becoming leaders of their own Citizens Enablement. However, even when successful in the short term collaborations should always strive for continuous improvement especially, if developers are designing citizen suitable products for the open market. All the projects shown in the Case Study portfolio are extremely successful in their own terms, especially to the citizens who have been a major controlling part of them and who own these developed products and facilities.

5.Leadership for Cultural Change

James picked up, quite far into his developing conversation with Peter, that no mention had been made about the importance of leadership in ensuring necessary cultural change for the better. For leadership is firstly required to enable citizens to develop a solution to their problems and issues that could work in their real world and then ensure whatever is developed stands any chance of actually working for all communities which might demand having the power to enact a solution that is allowed to exist or make wealth for a community. So for instance, as the Community Banking Case (Case Study 1, page 34) showed without Government allowing such banks to be built and able to act as ‘banks’ – which had never happened before in the UK – there would never have been Salford Moneyline etc. Similarly, the Action Learning development of the ‘Bouncing Higher’ learning development, in Case Study 6 (page 54), actually empowered small business managers to become more innovative, develop saleable products and actually become wealth creating in their own right; the North West Development Agency saw this as a fine way for bringing small businesses up to the leading edge of the market place and gave the project the go ahead to go further by enhancing the project. Such appropriate leadership is especially important for the academics, or others, wishing to support the citizens change for improvement, but then such leadership aspirations need to be passed onto the citizens themselves so they can continue the learning empowerment of others. This also respects that there may well be much resistance to any such change. Unfortunately all of us are in a cultural position which is deeply set and normally extremely stable. It is generated through many years of living in our own context, with those of like mind, sharing their views and behaviours. However, this is now challenged by what has happened to us all during Covid 19. So now may be the time for cultural change, catalysed by all sorts of emergencies including wars, famine, Covid 19 etc, but, to repeat even, now such change will not be simple.

If we are to achieve positive change in our cultural context, we will undoubtedly need to confront the stability of each cultures’ stance, and its value sets. For academics the existing culture, accepted at nearly every university, is deeply set and extremely resistant to change. Much as we might applaud the previously mentioned model of ‘excellence in diversity’ for education, in the long term there is little real evidence of such diversity actually occurring . So, the leaders of those trying to achieve change and their senior managers/councillors, they must recognise and allow for this. James was lucky, in his last senior role as PVC at Salford University, he had the full support of his bosses on what he was trying to achieve. But creating such a situation is not easy to achieve and can soon be lost without continued leadership to an agreed position. The ICCARUS project James led was heralded by a DTI study, who evaluated it, as one of the top three managed and led projects in the UK. This was because it was based on a powerful active listening approach which developed working systems of real value to ordinary citizens.

We will also need to create a world that gives voice to the kind of cultural specificity relating to academics supporting citizens – a federalism of collaborative interests that permit a necessary subsidiarity of its participants. In universities, as clearly revealed in Professor Nigel Lockett’s view of James changes at Salford University (2011), “there has always been a heroic ‘resistance movement’ to change of the kind envisaged he tried to enact in Salford University – many of his colleagues, tried to retain their existing academic status quo, with ‘partisan change enterprise groups in support of citizens’, battling with an ‘entrenched academic ‘culture’. So, embedding change for Citizens Enablement at Salford was not easy”, and will not be in most universities; rather it is a confrontation in the form of a ‘real world versus ivory tower’ discourse, or as one member of staff put it ‘we are academics, we sit in our ivory tower, do stuff and, as such you don’t understand what it’s like in the real world’. And within academe the cultural battle derives from opposing needs of scarce resources. And, while Salford’s appraisal and reward system ostensibly covered research, teaching, innovation and administration, it is still the research that is considered vital to ensure promotion.

As Prof. John Dewar, Vice-Chancellor and President, La Trobe University, a university trying to make the sort of changes suggested here said recently (2020), “universities serve many diverse functions and communities but first and foremost they are concerned with optimising their self-interest…. which leads to his case for a new approach University 4.0 – the ‘university for others’ – one outward looking, deeply connected to industry and the communities around it, and also committed to serving the needs of its students. In simple terms the reasons why we need to rethink the role of the university is firstly that the world of work, for which we are preparing students, is changing very quickly. We know that automation will make many current occupations obsolete; we also know that pathways into and through a working life are changing dramatically, with many of the traditional ladders into the workforce disappearing; and we know that the shelf life of skills and qualifications acquired through formal education at school and university is reducing very quickly. In short, the rapid change we see with digital technologies is rendering obsolete traditional approaches to qualifications and pedagogy.

The second reason for rethinking the role of a university lies in expectations concerning universities and economic development and growth. Research in universities has been an important source of innovation ever since they began but simply assuming that university research will somehow find its way into useful hands is no longer enough. More generally, a university’s social license to operate is increasingly dependent on its ability to demonstrate that it gives back to the community around it more directly than through the production of graduates. The result will be a much more active pursuit of applied university research, through deep industry partnerships, accelerator programs, incubators, and the like. This is reinforced by the fact that technological innovation now happens much faster and at a smaller scale that in the past the old methods of translating university research into commercial outcomes just take too long. This creates a need, and a space, for the rapid stimulation of ideas and their translation to commercial outcomes.

Universities are uniquely well placed to play this role their combination of smart people, sophisticated research infrastructure and, often, extensive real estate, position them well to act as the centre of precincts or innovation hubs involving physical co-location of the industry as well as fostering start-up businesses. The final reason is digital technology itself, which is actually a significant driver in the developments I have already stated. It also increases expectations about the availability and flexibility of the learning experience, while creating opportunities to respond to these challenges in new ways, and opens up other opportunities previously undreamt of”. And Universities must be seen more than as places of teaching where students re prepared for particular end goes in business or in civic life. After Covid-19 many Universities will strive simply to get more students to balance their books and to fill their halls of residence and try to develop new ways of teaching that are more cost effective to cut down costs. However, Universities are organisations of Higher Education, not Higher Teaching, and the word Education has its route in Latin, meaning ‘to draw out or lead out’ from within. We take this to mean, like in our proposal that Academics and others wishing to help citizens should try to draw out from them the undoubted skills each one has. So rather than just teach things more efficiently, they should seek ways to enable improved personal and self-learning for all – the essence of the proposal mentioned here

So Universities need to look at changing academic expectations to truly reflect the type of activities involved in enabling citizens; and fortunately for James, at least for his time in office he felt able to do that at Salford and hence the powerful cases showing success revealed in Part II. Unfortunately, the problem of trying to bring about change in a hierarchical organisation like a university or a local authority is, that those at the top can always take back any change they have allowed, especially if that leadership itself changes. This is why such change is so problematic and as champions of it come and go. New leaders are often unwilling to continue initiative started by their predecessors, as Nigel Lockett predicted in what happened at Salford.

Similarly, those from the community, citizens and small businesses, also feel themselves to be constrained by their existing culture, by their existing social, economic and political circumstances, by their world view and actions, or by their ways of seeing and acting in the world as learned responses to the complex nature of their lives, and by their existing expectations. In the face of an educated academic, even one wishing to help them, most citizens typically feel powerless and believe they are unable to compete creatively, innovatively or even to get the just desserts they think the deserve; they might say of what James is trying to achieve, ‘it’s not for the likes of us’. This was revealed in the Charleston and Lower Kersal project (Case Study 12, page 68) led by Tim Field, a citizen sensitive senior professional officer who was ready, willing and able to balance the creative, but often opposing views of the team of people managing it. In this case Tim’s leadership made all the difference and the local residents started to gain the confidence to try to develop better ways of working and better solutions to cope with what they knew to be their local problems and issues; this led to many things including a transformation of the environment in which they all lived for the good.

To some extent these two cultures of citizen and academe are also creating a pressure point between each other, seemingly blocking each other’s wants and ways of being. What we need to do is a sort of ‘cross infection’ of each other views and values so they each start respecting each other. This starts with caring and active listening by all parties in any collaboration

Peter believes the above are most useful passages in the paper showing typical constraints for both (academic) enablers and citizens. It portrays how cultures create blockers to change for improvement, which for parallel reasons become locked-into their existing ways by those wishing to remain part of their existing, but quite different, cultures. This is explained in the work of Mary Douglas, see earlier comments about her studies on page 1, at least to James, and shows how it also provides an excuse for inaction because of the fear of change

So creating learning change on both sides of this equation requires huge and sustained effort and a real desire for change. James was able to use his strong leadership, backed by his VC and Chair of Council, who he convinced that his proposed way, ‘was the only act in town’ for their university, especially with its particular staff’s capabilities. However, for James, and any other leaders trying to Enable Citizen to grow and develop, an approach is needed for academics to learn better how to motivate and reward staff to believe in a more meaningful way to do this; they also need to provide a structure and appropriate evaluatory mechanism which motivates and rewards those willing to try. It is also important to produce motivators and rewards to encourage citizens/communities to become stakeholders in their own future developments; during Covid 19 many have begun to recognise what may well be ‘at stake’ for them in a very different kind of future which they must learn must be more under their control – itself a wonderful motivator. To Peter, these are yet other key learning points: firstly to be vulnerable, and listening, as a leader and secondly build meaningful ways of providing rewards that truly encourage academics to actually try and thirdly to begin to be supportive of each other’s ways of trying.

Leadership for Enabling Citizens requires the leader’s own views, values and aspirations of need, and the developing learning processes, to be clear, consistent and repeated, especially in the way they are expressed so they respect the real constraints citizens have when they define their own problems they are willing to share in any development process. Such leaders need to provide a clear philosophical position statement for the change, which engenders a real commitment to an alternative kind of engagement. They must develop ways their colleagues can appropriately reflect on necessary new kinds of engagement, feeding back their reflections into their own developing processes. This becomes a virtuous circle, cycle or upward spiral for all academic staff. Again this demands active listening, and a caring response, to the citizens they are trying to support. And, to repeat, because it is so important, this in turn should drive the leaders to create structures which helps motivate and reward those staff who agree to follow the improved way – otherwise the existing culture will soon turn the process back to the old ways. So, we must establish the desire to apply Socratic principles of a genuine desire to understand the others’ position, articulate it to their satisfaction and take part in ‘co-operative argumentative dialogue’ between all the individuals in the development team so they recognise what precisely is at stake for all and what each individual is expected to engage in.

Similarly, we need to create an upward spiral of encouragement for citizens so they believe in themselves, and try the new and innovative for their own personal gain, as well as other colleague citizens or their local communities – circles of influence and circles of concern They need to believe they can move from a situation where they feel ‘there is one way for the ruling elite, and quite another for themselves’, to a culture of Enablement, where they are capable of securing the future they actually want. This is where sensitive and caring academic partners come into play, as they give confidence of what can be truly possible and work hard to avoid being limited by their own focused perspective; this may firstly be with their support and finally by achieving improved ways of citizen working by, and for, themselves. Such citizens need to learn how to believe in themselves, then to listen to other citizens in order to work out their needs as well, and try to lead a new change process themselves. This is not a trivial process without development teams being able to change the social, economic and political circumstances surrounding how they define the problem they are tackling, how they are seeking to address it and their ambitions/aspirations of all their efforts. Their reward will hopefully be the success they can achieve when they actually deliver improvements for themselves and other citizens. In effect, such citizens learn to become social entrepreneurs, citizen entrepreneurs or citizen innovators, adopting a new culture or cultural context where the challenge is to identify a truly objective ‘truth’.

For as Kevin McCloud – the architect, designer and tv pundit – recently pointed out, “we all like the same”, by which he meant the same things as those who inhabit our own culture or ‘sub-culture’ – some would say there is only one culture in society, but a series of differentiated sub-cultures which embody and embed quite different world views and social practices – in each sub-culture we want the same things, the same cars, the same houses etc reflecting our own same values. To McCloud, and us as authors, members of the same sub-culture typically want ‘the same’ as others in our own sub-culture; we are sustained by this while by the culture and this also guides our values and behaviour. These, in turn, affect what members of each sub-culture values and one of the difficulties is that (academic) enablers do recognise that they might not share the same values as their citizen partners or even approve of those they are working with. Indeed their own values may be in conflict with those they are trying to work with. We have found that a great deal when we act as facilitators/enablers ourselves, and it is difficult to work through. But we have to cope with this situation if as Enablers we are to help Citizens achieve in their own terms. And we do this by building up our understandings of each other’s culture, begin to determine shared desires, but they are as powerful and strong as any that are self-generated. Sometimes you may have to negotiate a temporarily agreed position even when people don’t have shared desires, interest and values; hopefully a temporary strategic alliance will eventually lead to a more specific change.

These lessons of trying to change a sub-culture, or more precisely trying to enable the sub-culture to truly adopt new ways of working, in order to achieve what their ‘culture’ tells them that they want, are the ones most difficult to develop, enact and embed. In the present context, they normally start from small, and fairly focused approaches, using the powerful language of the citizens themselves portraying a self-evident need that the rest of us clearly recognise; that is why Marcus Rashford’s call for the government to change its policy of providing food vouchers for poor children, has been so effective at creating change. It is also why we need to use the experiences, knowledge and skills of the Leonardo Ambassadors, and others in the know, to create similar successful ways of sustainable change.

James in fact developed an approach in his university, when a PVC, which he ‘defined as developing academic opportunities beyond means currently employed to the highest values’; this had a clear focus on Citizen Enablement and clearly worked for many of his staff, as can be seen in the next section. As one of his staff once said regarding the embedding of change he sought, ”the PVC is a fantastic advocate for the new enterprising way, but the problem is there is only one of him and he can’t be everywhere at the same time. The university’s next challenge is to ensure an adequate embedding at the grass-roots’. And this is the same challenge for all striving to develop cultural change within a university, a community or elsewhere. Another member of academic staff said, ‘my feeling is that because he (the PVC) is very enthusiastic, that drive is coming from there and that the Schools and Faculties, in which we all work, aren’t following with the same enthusiasm. The university needs to create a drive from the grass-root, as well as the top’, by understanding the WIFM (What’s in it for Me’ components of living). The review of James Powell’s Academic Developments by Professor Nigel Lockett and best portrayed by Case Studies – Generic Process A and B and other Case Studies, namely 6, 9,10,11,13 and 14 (pages, respectively) showed the effectiveness and appropriateness of his leadership with respect of Citizens Enablement.

Finally, Case Study 1 (page 34) on Community Banking, not only presents a study of the development but a fuller analysis in the use of the step-by-step approach Bob Paterson used to help citizens design, build and manage such Banks. So change of the kind suggested here in undoubtedly possible, but it requires a new kind of leadership which will try for such a change and be prepared to undertake the ‘heavy lifting’ that will be necessary to enact relevant change and to empower citizens.

The questioning framework shown below and the end of Generic Process A (page 26), is taken from the UPBEAT introductory manual, and shows a fairly complete representation of the fine sequencing of the approach we are proposing for those who truly wish to become Citizen Enablers and Empowerers; for we have found that asking the right questions, in the right sequence is the easiest way to achieve success. You start by asking the questions posed at the lower levels of the diagram and then work up step-by-step until you reach the highest honour of becoming a Global Steward. However, it must be stressed that you begin at the bottom in any new collaboration by tackling issues open to early consideration:

Information from The UPBEAT Use Manual

The star ‘My Leadership’ figure seen over shows, in summary and diagrammatic form, the essence of what we believe you need to develop to become a better leader in such circumstances. Much of this is about better leadership practice, which is shown in more detail in the Multimedia Learning Pack developed as part of the UPBEAT and PUMR work mentioned later in Generic Process Studies A and B (pages 26 & 31). This figure has been extended from Hall’s work on leadership (2012) with the numerals at the start of each characteristic representing roughly the sequence of leadership working in order. Such an order may be like ‘horses for courses’ and depend on the project and it’s developers.

In item 9 in the above figure, on good advice from Charles Savage, we have consciously tried to eliminate “competitive terminology”, so where I would once have used the term “teams” for those working together in collaborations, I am now calling them “Reflective Communities” (RefComs), because this encourages them to share their learnings also among and between all in the RefComs.

6.Focus of the leadership facilitation for Citizen Enablement to ensure success

Our studies on hundreds of best practice cases, written up as part of the UPBEAT project (Generic Process A, page 26) and in subsequent documents by the 10 Universities who took part in the UPBEAT exercise, have shown Academic Enablers must not only show leadership, but those leaders must focus on some key processes taken in turn that drive the Citizens to: firstly to become Enabled for themselves to work out a solution to their problem or issue, and then become Empowered to ensure their development is enacted to becomes a meaningfully, sustainably and cost-effectively delivered in the real world. Such necessary and critical behaviours can be learned, but start with Enablers being totally supportive of the citizens, or their small business equivalents, in learning how to make necessary change, and then actually make the decisions for themselves and undertake actions that will lead to their chosen goals. In short, the Enablers need to be: hands ready to help, not hands on or seeming to be continuously worrying; active listeners and quick responders; particularly support positive steps undertaken by the citizens; enable them to self-evaluate their own progress; build collectively to their own conclusions and working solutions.

In order to help Enablers processes of supporting necessary change James developed a self-evaluation tools, known as UPBEAT (see Generic Process A, page 26), which is shown in more detail in a many of case seen in Part II, and was developed into an approach, by the PASCAL International Observatory on Life Long Learning. The overall approach known by them as PUMR (PASCAL Universities for a Modern Renaissance) is shown in another case – Generic Process B, page 31). It also uses the UPBEAT evaluator matrix to help Citizen Enablers properly develop the necessary collaborative skills in their citizen partners; this is shown most poignantly in two other case studies – Contraception the Board Game – and the PUMR approach in the UCLL Belgium case study (Generic Processes A & B and Case Studies 2 & 3, pages 26 & 31respectively). These Case Studies presently exist in Part II of this presentation, however the intention is to make them accessible from the text directly when it is presented in digital form.

These evaluation tools and general approach are extremely similar in nature to the work of parallel successful developments in support of citizens enablement known as ‘positive deviance’, where facilitators supported the cross-fertilisation local positive behaviours to other citizens with much, and lasting, effect. A good example of this is shown in ‘The Positive Deviance Approach’ (2013) where Christopher Eldridge shows,, through a behaviour-influence analysis how in a Vietmanese community there were those who had uncommon, but successful, behaviours or strategies (the positive deviance) which enabled them enable them to find better solutions more common problems affecting their peers, at no extra cost. In the following we have summarised what we believe the general focus of the approach we are suggesting, linking our original approach with key elements of the positive deviance model since they add useful information to amplify certain points and issues valuable in all contexts; for simplicity, clarity and to remove the need for continuous quoting references to a minimum, any statements we draw from the Eldridge summary work are shown in italics.

- The first action in any development should be for the enabler to invite relevant citizens to work on the proposed joint development. Recognition and initiation are a key first step to ensure that: it is a project Citizens want to undertake for themselves; or after, active listening to the citizen’s needs by the Enablers, something the citizens would really like to learn to consider to change. So, all enquiries into such collaborative ventures should begin with an invitation from a community, or small businesses in another context (we assume from here on that when we talk about community henceforth we mean small businesses as well), that addresses an important problem they face, and not ones the Enabler just wants to work on themselves. This is an extremely important first step for ownership by citizens in the community of a process they must lead.

- Define the Problem, and key Citizens to work on it, CLEARLY: It is the citizens themselves that must be at the centre of defining the problem for themselves, then lead the change development or at least learn to lead its development. This will often lead to a problem definition that differs from the outside “expert” opinion of the situation or those in control through their status in the existing power/authority structure who hold the resources required for an alternative enactment in any proposed alternative solution with which they don’t agree. A quantitative baseline can be established by the community in this way and this baseline provides an opportunity for the community to reflect on their problem, given the evidence at hand, and also gives them a measure of their progress toward their own goals. Ideally, they will find a solution, or near solution to their problem locally, of at least with like-minded citizens nearby from which they can copy good practices; and learn from those with whom they will more easily communicate. This is also the beginning of their overall development process so they also identify other stakeholders and decision-makers regarding the issue at hand. Additional stakeholders and decision-makers will be pulled in throughout the process as they are identified. It is also a time when citizen/community talent is recognised and the performances needed to enable a suitable and sustainable solution to be found prior to development; the citizens should also decide what skills they need help with from the Enablers and other academics, and what skills they need to learn to ensure eventual success with their project; interestingly thjis is the basis of how citizens juries or assembles operate with effect. The problem remains of what to do in these situations of the asymmetric distribution of the power and it’s where collective collaborative working the socio-political situation come to the fore; ways, means and people have to be found to unblock such a situation to enable power to be ceeded to the citizens and communities so they become proper stakeholder in their own futures; this is shown poignantly in Case Study 14. In the Cases shown in Part II almost 50% of the projects had to explore and solve difficult and sensitive socio-political issues. In particular Case Studies 1, 2, 3, 6, 7, 9, 11,12 and 14 (on pages 34, 40, 46, 54, 57, 62, 66, 68 & 73 respectively) have strong political issues to confront which are discussed briefly in the cases themselves. However, one thing to stress is that finding the right people to help such empowerment changes to occur is vital in this respect if a project is to fully succeed.

- Determine any individual citizens, or groups in the community, that are already practicing a working solution, and thereby showing positive deviance: ideally the community will establish that there is positive deviance in their midst, and potential problems they can learn from and copy. Alternatively, citizens with their own new situation might learn from other contexts, by like-minded citizens or thinkers, of imaginative ideas that they can reposition in their own context for solving their own identified problem. This is partly why so many Case Studies were presented in Part II to show there are a plethora of solutions that can be copied, or repositioned, with effect, and there are indeed many other examples of similar successes by those using the principles of ‘positive deviance’. In this context, that when borrowing a best practice from elsewhere, it is important to recognise that what works in one place may not in another because of different conditions, circumstances and contexts; this is where the value of academics can come in to play as they can help translate ideas more easily as it’s part of their make-up. However, this sort of approach can then become a sensible citizen’s foresight to enable them to understand their own problem better and thus undertake the work necessary to form their own successful and sustainable solutions. The citizens have to understand this for themselves, and in their own language and ways, that what they will attempt to do is entirely possible. They also need to build capability in their own development team with the skills and structure to ensure a workable enterprise. Showing those in power that real, meaningful, sustainable and cost-effective example have been made to work elsewhere is a good way of convincing them to ceed their authority to an alternative solution which they can then learn to own as their constructive alternative. However, getting such cultural change is far from being easy, as this present approach continues to stress.

- Discover uncommon practices or behaviours: This is what occurs in all Positive Deviance Inquiries. If the community finds other best practices and identifies positive deviants, it can set out to use the relevant other behaviours (and attitudes or beliefs) to allow their use of this in their approach, thereby giving it a chance to succeed. The focus in all developments should be on successful strategies, not on making a hero of the person using the strategy. One important aspect is that where possible, positive deviants should be part of the delivery to the community needing change. This self-discovery of people/groups ‘just like me/us’ who have found successful solutions constitutes “social proof” that this problem can be overcome now, without the need for outside resources; where it’s not a matter of resources, it may still be necessary to consider what are legitimate acts within the prevailing political legal system. So the citizens might need to explore best practices and behaviours from complementary areas, applied research or citizen centred studies; all the time they need to develop solutions that do not alienate at least one of those who might be affected by any solution, and they can often do this by designing a constructive workable series of alternatives. Then they need to find ways and means of convincing those likely to be negative to any of their proposals that what they are suggesting can actually work for them. But again, this is often the most difficult part of any development. However, good data and appropriate observations using a language common to normal people, reflecting their normal ways of living and working, can make all the difference.

- Project design: Once the community has identified successful strategies, they must decide which ones they would like to adopt, and then design activities to help others access and practice these uncommon, positive, behaviours. Project design is not focused on professional spreading “best practices” but helping community members “act their way into a new way of thinking” through hands-on activities with their own best practices. They will also learn, with the help of the Enabler/Facilitator, how to develop relevant capabilities to achieve efficient and effective enterprise operations and how to continuously improve these working practices and solutions development by getting adequate feedback on their successes and positive developments.

- Monitoring and evaluation is key to success: The UPBEAT tools (Generic Process Study A, page 26) will enable the monitoring and evaluation of their project through a participatory process and support decision making in planning, designing and overseeing their progress in project developments; these have been incorporated into an overarching schema detailed in Generic Process B (page 31). These tools and their associated approach provides a clear and systematic guide for both Enablers and Citizens working together to properly understand their progress; it is similar in nature to the suite of techniques required for evidence-based decision-making which is now an established part of local democracy in the UK. Evaluatory feedback also helps development teams understand how to share, review and finalise their relationship with other stakeholders involved in their project. These include those in local regional and national authorities, especially key politicians and the tools give guidance on how to begin to deal with socio-political, as well as geo-environmental issues. Where possible this monitoring will be decided on and performed by the community and the further tools they create will be appropriate to their particular setting; see Cases Studies 1, 2, 3, 4,12,13 and 14 (on pages 34, 40, 46, 50, 68, 71 & 73 respectively). This can allow even illiterate community members to participate through pictorial monitoring forms or other appropriate tools; they may well be academically unqualified people but many of them are still extremely bright. Such evaluations allow the community to see the progress they are making towards their goals and reinforces the changes they are making in behaviours, attitudes, and beliefs. Acquiring the new skills necessary for the whole process of development, but particularly evaluation, requires time and effort from all parties in a collaboration. Not only to learn the skills but also to apply them. Such actions are particularly time-hungry and this must be borne in mind for citizens who may be time-poor as well as lacking other resources, including social capital.

- Cascading Improvement: As each citizen focused project develops, the citizens should strive to gain mastery over the role each of them plays in the team, gaining confidence, ease and elegance in the handling of complexity and the unexpected that will always come with any project development. They should then seek to use their own developing and creative leadership skills to inspire others, driving excellence for ‘real improvement’. At its highest level they should seek to become stewards of good practice acting with integrity and mutual respect, always striving for continuous improvement.

- Scaling up: The scaling up of our Citizen focused project may happen through many mechanisms: the “ripple effect” of other communities observing the success and engaging in this project itself, through the coordination of NGOs, or organizational development consultants. Whatever the way in which the project is scaled up, the process of community discovery of positive deviants in their midst remains vital to the acceptance of new behaviours, attitudes, and knowledge.

Using such a focus to the leadership, spelled out in more detail in the PUMR web site http://pumr.pascalobservatory.org should ensure Enablers can help Citizen design and develop high quality solutions to existing problems which become workable and sustainable solutions.

7.Conclusion to the step-by-step approach to Enabling Citizens

The cases cited in Part II all readily show how Citizen Enablement, and even Citizen Empowerment, is entirely possible for both academics (and other learning providers) and their citizen partners; all who can learn to work together in powerful and co-creative ways. Such processes can also be mutually beneficial and for some universities answer many academics desire for ‘excellence in diversity’. James believes it is important that outstanding, and dedicated, academic leaders are prepared to change their ways of education for Citizen Enablement; they, and their senior managers, need to return their Universities into systemic and systematic places of learning, places where citizens feel comfortable to explore their own futures in a constructive way. Our Case Studies also show that to be successful, Academic Leader Enablers, in such collaborations, must:

- be intensely professional, but have absolute personal humility

- learn how to harness their own ability to influence others (requisite power), being motivator and team builder, while be able to actively listen and respond to their needs

- ask challenging & penetrating questions of the status quo

- learn to live with risk because the organisation/project needs this as opportunities develop

- learn to lead yourself and then spread that leadership to other team members, so they too can help the team shine:

- deliver your practice, into everyone’s practice, which become the practice; and create contexts where the positive successes of any development can be seen by others providing separate motivation

- facilitate others and network building

- recognise leadership is place dependant and context responding

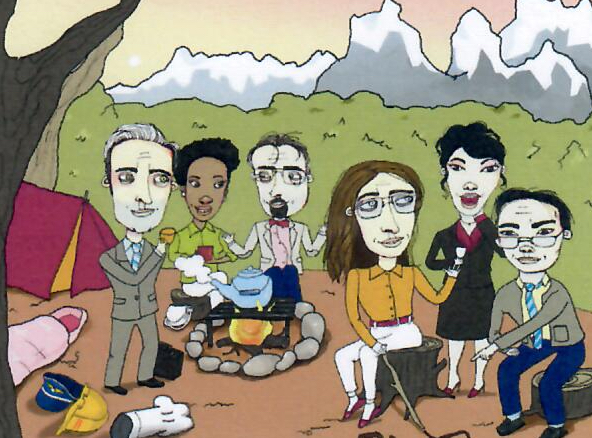

Normal citizens, who were once scared to try the new, can find a voice for their needs and wants, and many have become social entrepreneurs in their own right, with the right support. Some we have seen in the case studies have even begun to lead new projects for themselves, with others; they become, in effect, their own Citizen Enablers. The harmony of a great collaboration is shown in the car

The citizens friendly environments, Academic Enablers must try to develop

What we may well be suggesting overall is a new model of active welfare, in which, as Charley Leadbetter from DEMOS suggested in 1997, ‘citizens are encouraged to take more responsibility for their lives.’ In such new ways of working, ‘schemes of development will no longer be seen in terms of a sum of money or package of entitlements. Rather, they will embrace a philosophy where welfare and wellbeing become inseparable from self-control and self-confidence. It could become the new creative individualism, which is at odds with most citizen’s normal passive, recipient culture, provided in the Western world by most welfare states and ‘mass consumption capital’ appears to have the same stultifying effect in terms of dependency ‘culture’.

8.Summary of our Human Futures after Covid 19